TLDR:

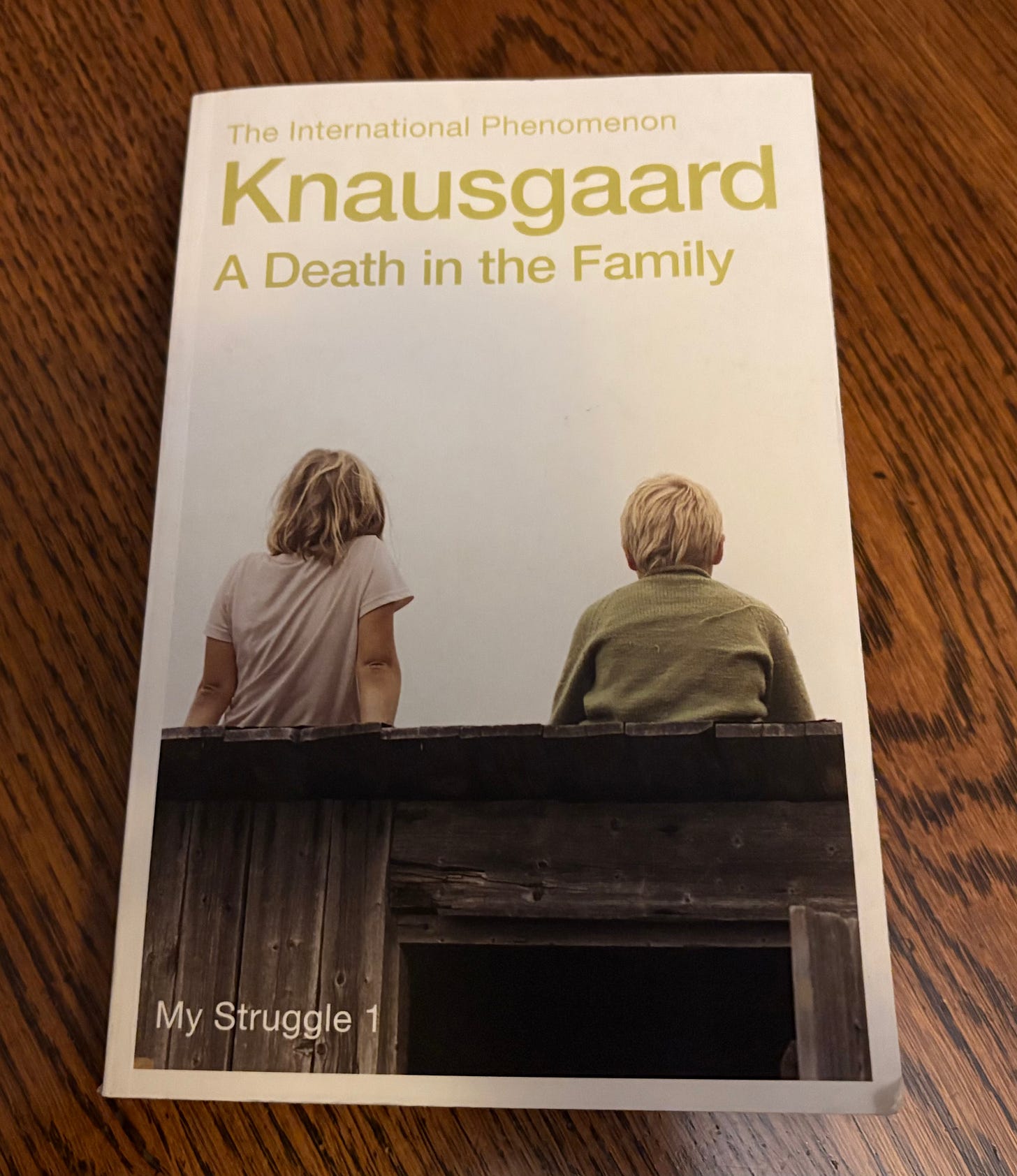

A Death in the Family, Karl Ove Knausgaard

Daniel Dennett interviewed by Nigel Warburton, Five Books

Can We Solve the Mind-Body Problem?, Colin McGinn

The Door in the Wall, H.G. Wells

Romeo + Juliet, Baz Luhrmann

This is the sixth in a regular Sunday series.1 As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond ’things I’ve been reading’, towards the end.

1) A Death in the Family (2009) is the first book in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s set of six ‘autobiographical novels’, My Struggle. Considering the cultural status attained by these books (they’re clear contenders for the most discussed of the century), I could claim I’m unsure why it took me so long to read any. But I have a pretty strong aversion to consensus aesthetic approval, so I assume that’s to blame.

A Death in the Family is the realist chronicling of a writer’s attempts to make sense of himself, the world around him, and how his making sense of these things affects his writing and his personal relationships. I finished reading this book today, so I want to think on it some more. But I loved how even its most descriptive sections — whether focused on bathroom sinks, airport runways, or snowy Norwegian forests — attain an understated casual clarity. Take this phrase: “while the huge surfaces illuminated by the sunset did not shine or gleam or have a reddish glow, as they could do, rather they seemed as if they had been dipped in some liquid”. For me, the inclusion of the word “some” is what makes Knausgaard’s writing great: “some” brings it back down to Earth. Knausgaard never luxuriates; he states and he reflects.

That said, every so often, Knausgaard interrupts his episodic everyday style to offer short essays on aesthetics, or time, or other explicitly philosophical matters. Some of these essays I liked. Others, which I should probably read again, felt forced and distracting. For now, however, what I’m left with are interactions at the corner shop, toppings laid out for open sandwiches, and guys mysteriously managing to open beer bottles with lighters. That’s because so much of what goes on in this book is banal, in the best possible way. This banality does more than enable Knausgaard’s superlative realism. Every so often, some passing detail — the comparison of alcoholics with vampires, or the throwaway last-minute revelation of grandparental rejection — makes you reassess it all, and I don’t just mean the book.

2) The introductory interactions of this 2023 Five Books ‘favourite books’ article, in which Nigel Warburton interviews Daniel Dennett, represent public philosophy at its best. Coming before the business of the article proper, these interactions read, to me, like a real-life chat between real philosophers — even though it’s a chat with the explicit goal of sharing the distinctness of Dennett in an accessible and enjoyable way.

In response to Warburton’s incisive questions, Dennett comes across as modest as well as fun, emphasising the fortunate contingencies of his life, and his indebtedness to the thinkers around him. I like his use of language, too. Arguing with Ryle is compared to “punching a pillow”, and Nagel and Lewis are “fast company”. He uses “phisticuffs” and “mongering” in the same sentence, and he gets away with it! Indeed, while I almost always prefer consuming words by reading rather than listening, I’d quite like to hear an audio recording of this conversation. I’ll end by admitting that — although I recently wrote admiringly about Where Am I? — I’ve never got far with much of Dennett’s work. This interview made me reconsider.

3) In Can We Solve the Mind-Body Problem? (1989), Colin McGinn argues that we’re wasting our time trying to “resolve the mystery” of consciousness. It’s not, he tells us, that we haven’t found the solution to the problem, yet. It’s that we can’t. That is, in the same way that being inside a box prevents you from seeing the box from outside, McGinn believes there’s something about the nature of human consciousness that prevents us humans from fully understanding it. “Our concepts of consciousness just are inherently constrained by our own form of consciousness,” McGinn contends, “so that any theory the understanding of which required us to transcend these constraints would ipso facto be inaccessible to us”. This is what McGinn terms “cognitive closure”. And, in particular, the missing piece of the puzzle to which he thinks we’re ‘cognitively closed’ is awareness of the brain property that makes sense of the mind-body relation. This property, McGinn feels assured, is not “miraculous” — just as he feels assured that there “has to be some explanation for how brains subserve minds”.

Beyond these over-confident asides (which made me think of Dennett’s ‘surely alarm’!), the main concern I have with McGinn’s paper, however, is that it often feels as if he’s depending on the fact (as he presents it!) that we haven’t yet solved a problem, in order to argue that we aren’t able to do so. This feels like sophistry. Nonetheless, it’s an elegant and original paper, which offers a strong — albeit somewhat depressing — ‘solution’ to a notoriously hard problem.2

4) H.G. Wells’ The Door in the Wall (1906) is the short story of a man whose one-time childhood experience of bliss lends dissatisfaction to the rest of his life. If you’re into ‘crossed with’ descriptions, then it’s a bit like Goblin Market crossed with The Secret Garden. I reread it every few years, and think about it every time I see a door that’s green.

5) I rewatched Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996) this week, having not seen it since the 1990s. From the opening news-reading of the prologue, I loved it then, and I love it now. I can’t think of Shakespeare done better.

I’m publishing this after midnight UK time, but it’s still Sunday in some other places..

I need to read the My Struggle series again, I loved them the first time around.