five top things i’ve been reading (twenty-second edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

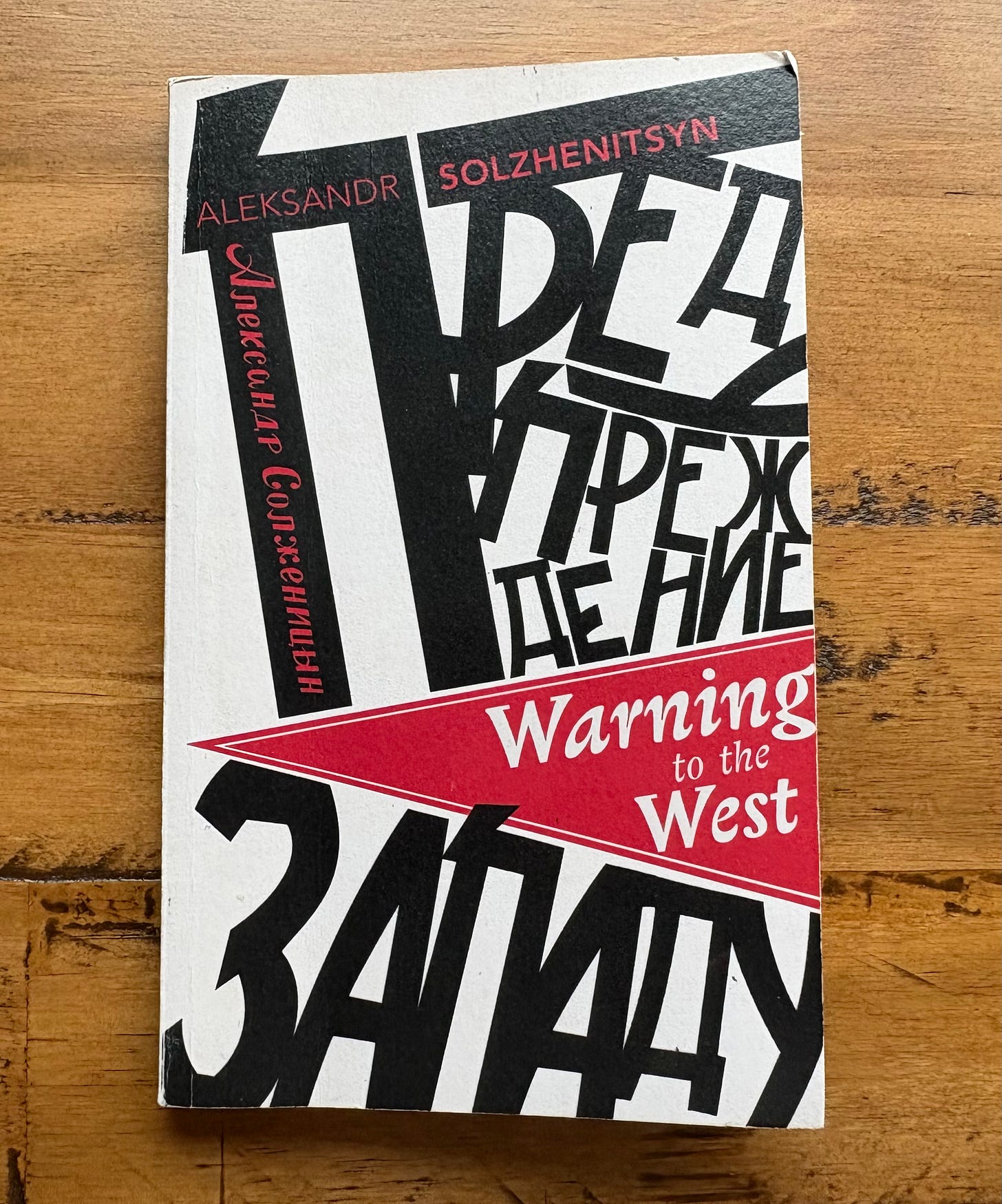

Speech by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, June 30, 1975

My Interview With Galen Strawson, Part I, J.P. Andrew

Wittgenstein and the Paradoxes at the Limits of Language, Graham Priest & Oliver Adelson

The Last Letter, Daniel R. Brunstetter

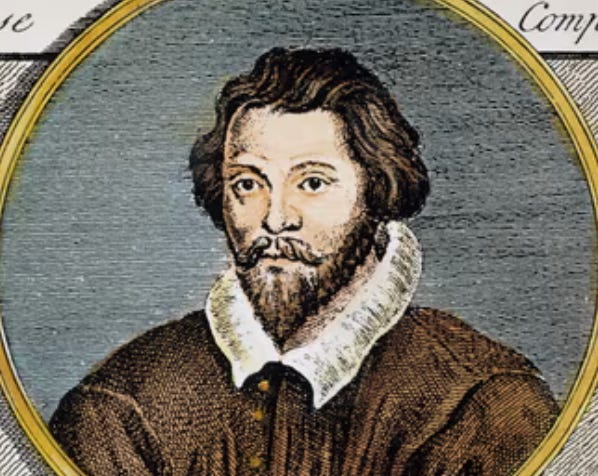

Sing Joyfully, William Byrd, sung by the Tallis Scholars

This is the twenty-second in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) Yesterday, I read a speech that the great novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn gave in 1975 to a DC audience convened by the US labor union leader George Meany. The New York Times report on the event describes Meany as someone who “has strongly attacked the policy of seeking accommodation with the Soviet Union”. This idea of ‘seeking accommodation’ is central to Solzhenitsyn’s speech.

As you’d expect, it’s a particularly powerful speech, full of important details about the brutal oppression Solzhenitsyn and his compatriots suffered under the Soviet regime. It’s a speech that all communist apologists should read. But it’s also a speech that’s so idealist in nature that its condemnation of the — then extremely recent — American withdrawal from Vietnam is effectively absolute.

“We couldn’t understand the flabbiness of the truce,” Solzhenitsyn tells his audience. He then expresses similar disturbance at the idea of America ‘giving up’ on other countries:

“We already hear voices in your country and in the West: ‘Give up Korea and let’s live quietly. Give up Portugal, of course; give up Japan, give up Israel, give up Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, give up ten more African countries. Just let us live in peace and quiet. Let us drive our big cars on our splendid highways; let us play tennis and golf unperturbed; let us mix our cocktails as we are accustomed to doing; let us see the beautiful smile and a glass of wine on every page of our magazines’.”

Underpinning this reproval is Solzhenitsyn’s belief that, as he tells his American listeners, “Whether you like it or not, the course of history has made you the leaders of the world”. In this context, Solzhenitsyn makes three criticisms of America. First, that America is failing to meet its special obligations to free the oppressed. Second, that America isn’t just failing to free these people, but is constraining them in their own slow struggle for freedom, by persistently seeking “concessions” with their oppressors. And third, that America has been known to go even further than capitulating to these oppressors, by selling them the technological goods that have extended their capacity for oppression.

Of course, the standard response to Solzhenitsyn’s first criticism — at least these days, post-Iraq — is that America gradually came to realise that freeing the oppressed peoples of the world wasn’t feasible. A variant on this response is that, in each particular case, America realised that the human cost of continuing to fail to free the oppressed had become too high. There are further variants on this standard response, including one focused on the unintended consequences of American interventionism, and another focused on legitimacy concerns. But as a response to Solzhenitsyn, it can be strengthened by acknowledging the particular oppression that occurs when people are treated as tools of war.

That is, Solzhenitsyn’s case for American intervention is supposedly grounded in the American obligation to protect the oppressed, but nowhere does he account for the oppression suffered by American conscripts in many of America’s interventionist wars. I don’t intend, by this, to downplay the harms suffered by the many other people involved in these wars, including conscripts from other nations, and volunteers and civilians on all sides. Rather, I want to emphasise that if you care about freedom from oppression, then regardless of whether Solzhenitsyn was right that America should have fought and continued to fight such wars, you can’t ignore the thousands of American men who were coerced into fighting, suffering, and often dying, in the name of liberating others.

Like most people, I find it extremely hard to come to satisfactory conclusions about the ethics of war. Over the last twenty years, I’ve gone from being a hardcore liberal interventionist, to wanting (and so far failing) to become a pacifist. But I find it easy to conclude that the state would be acting oppressively if it coerced me into defending myself by making me into a tool of war — never mind if it coerced me into defending other people in such a way, and particularly people I’d never even met. I mean, I hope I’d come to the rescue of a stranger, if the stranger needed me, and I was able. But it’s not for the state to force me to do such a thing — a fortiori if it involved killing others.

Acknowledging the wrongs of this particular kind of oppression not only strengthens the ‘human cost’ constraint of war, therefore, it strengthens the ‘feasibility’ constraint, too. That is, if the state can’t force its citizens to fight, then how many wars are feasible? And how many wars would continue to remain feasible, over time? To what extent does interventionism, in particular, depend on the morally impossible ‘need’ for conscription? The answers to these questions may change in light of the technological developments that have taken place since Solzhenitsyn passed away. Maybe they have changed already. But for Solzhenitsyn at least, war turned on human combat.

Turning to Solzhenitsyn’s second criticism — about American ‘concession-making’ — we can pose another response that hinges on acknowledgement of the constraints of feasibility and human cost. What can you do except compromise, if you’ve accepted that you can’t fight, or you can’t win? Ok, you could’ve refused to get involved in the first place. Or you could give in entirely. But those are just different kinds of concession. Something similar applies to Solzhenitsyn’s third criticism, too. That is, surely it’s right to criticise America for selling weapons to tyrants. But on Solzhenitsyn’s account, America also ‘collaborates’ when it gives aid to the oppressed, because doing so lightens the burden on their oppressors. So it starts to seem that sometimes, for Solzhenitsyn, America’s only option is to fight to the death.

Perhaps some hope appears, however, in his conception of “true détente”? Here, first he tells us that true détente can only be entered into by states that have disarmed themselves of any weapons they’d used against their citizens, as well as any weapons of war. Second, that true détente must come with the backing of democracy: its parties thereby held to account by the people, the press, and the parliament. And finally, that true détente is inconsistent with the continuation of “malevolent propaganda”.

These are crucial goals. I’d even count the second as a necessary feature of the legitimate state. Yet, as Solzhenitsyn himself questions elsewhere in the speech, has there ever been a state that’s really counted as a democracy? Because if not, then there’s never been a state that could’ve been party to ‘true détente’. Moreover if, for instance, we were to take the US and UK, at some point in time, both to count as democracies, then would they really need a détente? In other words, Solzhenitsyn’s conception of détente comes up against the ‘democratic peace thesis’: the descriptive claim that democratic nations don’t go to war with each other. Then finally, we come back to the impossible ‘need’ for conscription. That is, perhaps democratic nations would be good partners in true détente. But true democracies — if they are to oppose oppression — are not places that force people to fight.

When it comes down to it, Solzhenitsyn’s view is that the good guy must always be there to save the day. But one problem with the ‘good guy’ solution is there might be no such guy. Perhaps there can be no such guy! And even if there were, he might not be able to save the day. Of course, if you’re willing to take wars as numbers games, on which the ‘winning’ state is the one with sufficient people left, no matter how few, to compel the other side into loss, then perhaps winning is always a possibility. But if you predicate winning on maintaining respect for individual freedom, then winning will not always be possible. Where this leaves us is an unhappy place. But happiness cannot be the only value.

2) I really enjoyed this new piece on J.P. Andrew’s Substack, in which he interviews Galen Strawson. It’s interesting and fun and clear. Much of it focuses on Strawson’s commitment to panpsychism — a theory on which consciousness, as a fundamental part of the universe, exists in even the most basic things, like atoms, in at least some simple form.

Panpsychism is best known for being used by its exponents to offer solutions to the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness. This problem lies in the interrelation of the physicality of the human body and the subjectivity of human experience. At its heart is a question about causality, formulated by David Chalmers as, “Why should physical processing give rise to a rich inner life”?

Now, I’ll admit up front that I think panpsychism is mental (yes, that’s a philosophy joke), even though my friend Philip Goff has done a nice job of rehabilitating it as a mainstream philosophical position. In brief, I don’t buy panpsychism partly because I can’t get my head/mind around the idea that non-living things could be conscious, and partly because panpsychism means giving in to the physicalists. But, as it happens, Strawson — who’s been pushing panpsychism for even longer than Philip — is pretty upfront in this piece about the serious problems panpsychism faces.

Most famous of these is the ‘combination problem’. This is the objection that points out that even if basic particles did have some simple kind of consciousness, then it’d still be a jump to conclude that together these particles could give rise to the ‘rich’ kind of consciousness experienced by human beings. In other words, ‘Ok, I’ll accept that consciousness is fundamental, but how does that solve the mind-body problem!?’. In the interview, Strawson accepts the power of the combination problem, admitting that combination “must happen, but I don’t know how”. He concludes by calling panpsychism “the least worst metaphysical view”.1

3) Here’s another interview piece I recently enjoyed. It’s from the APA blog, and involves Oliver Adelson questioning Graham Priest about the limits of language. I’ll admit that I didn’t find Priest particularly elucidatory on the central topic of the interview: the paradox of talking about what you can't talk about. If anything, reading his answers pushed me further towards one placeholder view I hold on the topic, which is that if there really are things in the world that we’re unable to talk about,2 then of course we can still talk about them, because ‘talk about’ can mean different things.

So, one way we can ‘talk about’ such things is analogous to the way in which you can reveal that you have a secret without revealing the content of that secret. I know this doesn't get us all the way on the ‘talking about’ problem! But I think it does get us some of the way on some of the examples Priest puzzles about in this piece, and which he addresses by resorting to dialetheism (i.e., ‘Hey, don’t worry, contradictions can be ok!’). Take, for instance, the example he gives from Kant. Priest says that Kant’s “view commits him to there being dinge an sich, things to which you can’t apply the categories. But in talking about these things you have to apply the categories”. I find this comment ambiguous. But if what Priest means is something like, ‘Oh no, Kant claims the noumenon is inaccessible to us, but he talks about it anyway!’, then I don’t see that as a case of the paradox at hand, any more than stating the paradox is!

Anyway, there are some nice moments in this piece. I especially liked the section near the end where Priest talks about the value of engaging with philosophers from history. It’s a “very sad view”, he tells us, on which studying the history of philosophy is taken to have no philosophical value. This is because, he continues, “philosophy is always going to be a dialogue between people who disagree. And great philosophers who are now dead and therefore not part of the contemporary discussion have really interesting views. These are smart bastards.” So true.

4) I’ve already subjected you to a lot of words, so here’s a piece that needs no analysis. Or rather, the letters quoted in this piece — final letters written by men condemned to die — can stand for themselves.

5) I listened to a load of recordings of Byrd Sing Joyfully this weekend. This one, by the Tallis Scholars, is the best.

I haven’t really done justice to the charm of this interview by focusing solely on Strawson’s panpsychist takes, and worse by using that as a route into talking about the topic more generally! But I hope you’ll go and read it.

I’m planning to update this view when I find proper time to think about these things..

The link to letters people wrote reminds me of a book I love called "Japanese death poems", basically a collection of haikus written shortly before death. Very interesting to read things written at such an important moment for people.

Thanks for this thoughtful reflection on Solzhenitsyn’s speech. I haven’t read the full text myself, but your summary makes it sound like Solzhenitsyn was urging America not to abandon its telos. He seems to see the United States not just as a global superpower, but as a moral example, a nation committed to liberty and resistance to tyranny.

What stood out in your response is the conflict between that mission and the means used to carry it out, particularly the use of conscription. There is a deep irony in a country founded on individual rights forcing its citizens to fight in the name of securing those rights for others. It raises a difficult question: can a liberal democracy pursue global justice without violating the freedoms it claims to uphold?

I am currently reading MacIntyre’s After Virtue, and I find it relevant to this problem. He critiques how modern moral reasoning has fractured into isolated parts, with utilitarian and deontological arguments pulling in different directions. We use moral language to justify or condemn, but we no longer share a coherent narrative about the good.

Both Solzhenitsyn’s moral urgency and your concern for coerced sacrifice may reflect this fragmentation. They appeal to different ethical frameworks, but neither feels fully grounded in a shared moral tradition. MacIntyre’s response, as I understand it so far, is to recover a more Aristotelian view of ethics, one based in practices, community, and the cultivation of virtue aimed at a common good.

I wonder if that framework might offer a better way to assess not only whether intervention is justified, but also what kind of people and political communities we need to be in order to act justly. Have you read MacIntyre? I would be curious to hear your thoughts, especially in relation to the questions you raised about legitimacy, sacrifice, and moral authority.