five top things i’ve been reading (twenty-fourth edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

The Cold Equations, Tom Godwin

The Archive of Feelings, Peter Stamm

The Regensburg Address, Pope Benedict XVI

Philosophers whose prose is so dreamy it won’t even send you to sleep, Amos Wollen

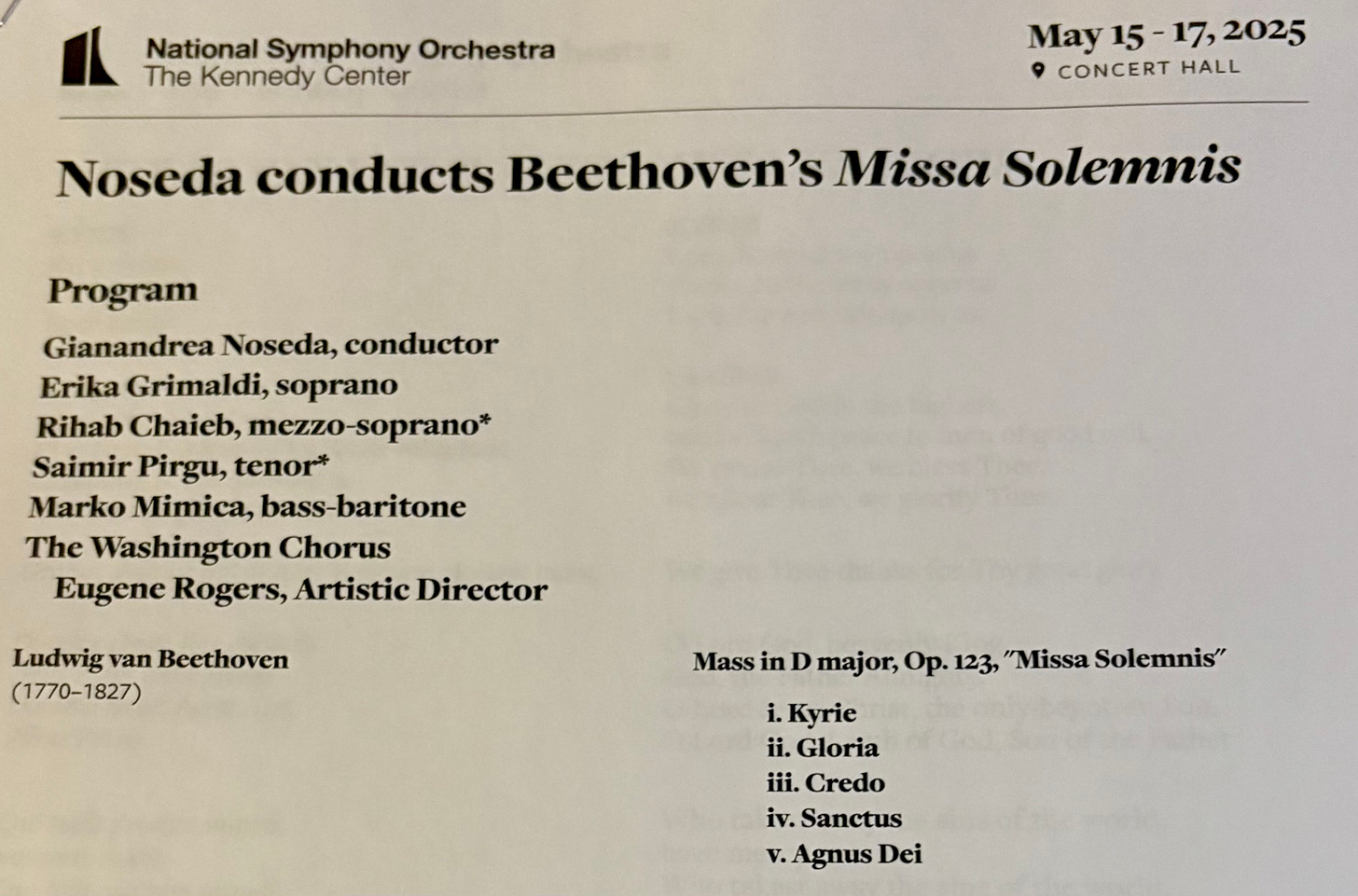

Beethoven, Missa Solemnis, conducted by Gianandrea Noseda, Kennedy Center

This is the twenty-fourth in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) The Cold Equations is a short story by Tom Godwin, and it’s kind of a thought experiment. I say ‘kind of’ because while this story shares many of the properties of classic thought experiments, it fails to pose a difficult philosophical question.

Indeed, central to The Cold Equations is the idea that no such question is posed. As its reader, you aren’t called upon to decide between letting the trolley car hit five people, or redirecting it to hit ‘only’ one. And you aren’t called upon to decide whether to push the fat man off the bridge. You aren’t even called upon to decide something much less morally urgent, like whether you’d survive teleportation, or whether if Brownson had Brown’s brain and Robinson’s body then Brownson would be Brown or Robinson or neither or both!

Nope. In The Cold Equations, the pilot of the emergency dispatch spaceship has no option but to eject the stowaway. (Sorry, lots more spoilers ahead.) This means that the stowaway will certainly die of exposure to the space vacuum. And it means that you, the reader, have nothing to do in this story but stand by and cry. After all, you’ve been told several times that a physical law has “decreed” that “h amount of fuel will power an [emergency dispatch spaceship] with a mass of m safely to its destination”, and that another physical law has “decreed” that “h amount of fuel will not power an [emergency dispatch spaceship] with a mass of m plus x safely to its destination”. So you know there’s no option. You know, as well as the pilot does, that since the stowaway sadly equals x, therefore the stowaway’s death must be inevitable, because otherwise the spaceship will not reach its destination safely. Indeed, that it will crash. And that “no amount of human sympathy” will change this.

What’s more, any details that have increased your sympathy have been explicitly offset by Godwin to underline the futility of the situation. So, ok, the stowaway turned out to be a polite teenage girl called Marilyn, hitching a ride towards her beloved brother, rather than an angry highwayman, seeking to commandeer the spaceship for nefarious purposes. But of course Marilyn weighs just enough to unbalance the equation! And ok, Marilyn didn’t know that stowing away would entail her death. But of course there was a handy ‘no entry’ sign on the spaceship’s door! And ok, there are other people in this story whose lives are also at stake: six sick men in urgent need of the medicine the spaceship is transporting. But of course none of those men can die instead of Marilyn, because they’re miles away, and the pilot can’t take Marilyn’s place either, because we can assume she doesn’t know how to fly a spaceship!

It seems, therefore, that any difficult philosophical question this story poses must lie at a deeper level than everyday practical reasoning. It's not: should you pull the lever in the trolley problem? It’s: why isn't there a third trolley track? Yet even this meta-level appears to have been tied up by Godwin! Once you’ve worked out that the obstacle to Marilyn’s survival isn’t the necessities of physics, but the lack of slack that’s been left by human decision-makers, then you’re hit with a secondary argument, hinging on a different, circumstantial, kind of necessity. “[The] laws of the space frontier”, you’re told, “must of necessity be as hard and relentless as the environment that gave them birth.”

In other words, the underlying reason there’s no spare fuel on the spaceship isn’t, of course, the laws of physics: it’s because emergency conditions obtain! And fair enough, right? I mean, this is why there are no friendly spaceships nearby to offer Marilyn a berth. It’s even why she hasn’t seen her beloved brother in a while: he’s out on the frontier, himself. So mightn’t it also be why the pilot is permitted to eject Marilyn into space? In times of emergency, necessity wins out!

At this point, I could discuss the rule-of-law publicity condition that requires lawmakers to provide sufficiently good information to those bound by their laws. (The sign on the spaceship door was not enough!) Or, I could make more explicit the dangers of the is/ought category error. Instead, however, I want to talk further about thought experiments.

To my mind, the core value of a thought experiment lies not in exposing the demands of practical reasoning — not, that is, in preparing you for some nightmarish real-world moment when, astonishingly, you find yourself actually staring out at the diverging trolley tracks, lever in hand. No, the core value of a thought experiment lies in its capacity to isolate philosophical ideas for testing. To this end, the trolley problem isn’t really about picking a track; it’s about whether morality reduces to a specific kind of maths problem. And to this end, the philosophical function of The Cold Equations can be seen as testing the permissibility of a kind of ‘emergency morality’. That is, the idea that, in certain harsh conditions, we can do horrible things with impunity — not because doing these things is generally ok, as per the trolleyist’s everyday consequentialism, but because there’s simply no other option.

Now, it’s clear that the pilot of the spaceship — whose name we learn is Barton, but who for the most part is reduced to an abstract ‘he’ — is heavily bought into emergency morality. Barton is so bought into emergency morality that, although he sympathises with Marilyn, his actions are the actions of someone who has entirely outsourced his moral reasoning. For Barton, therefore, the frontier is not the ‘each man for himself’ state of nature. It’s a domain of total top-down control. Indeed, the single ‘option’ Barton believes he holds is to confirm the relevant rules with his superiors, which he does as soon as he finds Marilyn aboard the spaceship. So Barton never even considers the real alternative to killing Marilyn. That is, Barton never recognises he has the option to die alongside Marilyn, in respect of their shared humanity, and in protest against the tyranny of the emergency morality that’s been imposed upon him.

But wait a second, you shout! Didn’t Marilyn walk into the air lock of her own volition, ready to be ejected by Barton? Doesn’t this imply she’d accepted that dying was the right thing to do, for Barton’s sake and the sake of the six sick men, whose lives depended on her death? Shouldn’t we interpret Marilyn’s death as suicide, therefore, rather than concluding she was killed by Barton? After all, in the circumstances, doesn’t it seem that walking into the air lock was the right thing for Marilyn to have done? Probably. But there’s a serious problem with the ‘suicide’ interpretation, nonetheless — which is that Barton wouldn’t have let Marilyn ‘choose’ otherwise. That is, it’s unspoken, but surely it’s true, that if Marilyn hadn’t walked into the air lock of her own volition, then Barton would have put her there by force.

So Barton does face a choice, after all. And the answer to this choice lies not in weighing up the value of the lives of the six men he’s been sent to save. It lies in something prior to his capacity to save those six men: in the strength of his obligation to refuse to kill Marilyn. I think the most hard-hitting feature of The Cold Equations is that this choice is never made explicit. The option of shared sacrifice is never even discussed! Marilyn doesn't struggle, or ask Barton to go into the air lock with her: she gives in, as has he. The inhumanity of emergency morality is made stark, to this end, by the inevitabilist framing accepted by both killer and victim. We are susceptible to these norms, The Cold Equations tells us.

Normal thought experiments pose difficult questions as difficult questions: questions focused on complicated matters of reasoning, the difficulties of which are human difficulties, in the sense of difficulties that are natural for us humans to identify and to struggle with. Kill one man or let six die? Regardless of the correct answer as to whether Barton should’ve chosen to go down with his ship rather than to kill Marilyn, the question simply doesn’t arise in the story. When you don't see the problem, it's often too late.

2) Last year, I read Peter Stamm’s Seven Years (2009), and I enjoyed it so much — both in content and style — that the next of his novels I tried was perhaps bound to disappoint me. Perhaps not. Either way, while reading The Archive of Feelings (2023) this weekend, my overriding feeling was disappointment. It’s the story of an unnamed man who, having been sacked from his job as an archivist, finds himself with an opportunity to re-encounter the woman he’s been longing after for decades. This sounds like a promising Stamm-ish set-up. But its language use is less efficient than Seven Years, and its plotting is too focused.

I kept on reading The Archive of Feelings, however, and it’s still there in the back of my mind, so here are three quick takeaways. First, I assume that a crucial quality of the main character of this novel, at least in terms of explaining many of the choices we see him make, is that he’s autistic. I find it interesting that this is unspoken. Second, I really didn’t like the over-kill methods that Stamm uses for signifying which sections of the novel are imaginary (within its characters’ world), though I do get that these help to ensure the reader shares in the characters’ sense of release when reality finally hits. And third, I probably wouldn’t recommend that you read this novel if you haven’t already read Seven Years. This is mainly because I think you should read that instead, but also because you mightn’t stick with this otherwise — and that’d be a shame.

3) In 2006, Pope Benedict XVI gave a lecture to “the representatives of science” at the University of Regensburg, entitled Faith, Reason and the University, which has since become known as the Regensburg Address. The central thesis of this address is that it’s important to acknowledge the interaction of Christianity with Greek philosophy — because this is a matter of historical fact, because thinking about their interaction can help us to understand the relation between faith and reason, and because the faith-reason relation serves to justify the study of theology within the university institution. As a former Christian with an interest in Greek philosophy, I found much in this address to enjoy, as well as some theological premises I wish I still believed in.

I liked, in particular, Benedict’s commitment to arguing against the empirical sciences as the only route to truth. I strongly believe that many truths, minimally all moral truths, are found not through the empirical method, but through assessing the strength of values-based arguments. And that some of these truths, which are often hard to ascertain, relate to what exactly it is that makes moral truths true, and the role that reason plays within this. I’ve previously found much value in John Finnis’s writing about these matters, especially within Natural Law and Natural Rights (1980); I’m glad to have read the complementary thoughts of Benedict, another modern Catholic philosopher.

4) I enjoyed this recent Substack piece by Amos Wollen. The central idea of Wollen’s piece is that, contrary to popular opinion, some analytic philosophers can write beautifully. He even lists his top ten “dreamy” analytic-philosopher prose stylists, providing a writing sample of each. Now, I’m one of those crazy people who loves reading analytic philosophy more than doing pretty much anything else: I read it to relax as well as for excitement. And I find bad prose style neither relaxing nor exciting. Beyond that, many of my favourite prose stylists are analytic philosophers. So I was already on board with Wollen’s idea. At the more specific level, however, I strongly agree with some of his picks (though definitely not all of them!). If I made my own list, I’d definitely include, as Wollen does, Judith Jarvis Thomson, David Lewis, and Peter van Inwagen. A fun game.

5) On Saturday night, I went to an excellent Beethoven Missa Solemnis at the Kennedy Center. I wasn’t fully convinced by the placing of the soloists between the choir and the orchestra: 90 per cent of the time this pulled everything together. But the NSO, as ever, was persistently great.