TLDR:

Conscious Artificial Intelligence and Biological Naturalism, Anil Seth

Ranking the 25 Coolest Things in Space So Far During the 21st Century, Eric Berger

Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?, Edmund Gettier

The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, Ursula Le Guin

Fancy, Francis Poulenc

This is the fourth in a regular Sunday series. As with the previous three editions, I’ll move beyond ‘things I’ve been reading’ in the final item.

1) In his recent preprint, Conscious Artificial Intelligence and Biological Naturalism, neuroscientist Anil Seth argues that AIs are unlikely ever to gain consciousness unless their nature becomes much more like the nature of living things.1

First, Seth carefully argues against the more mechanistic route to AI consciousness proposed by computational functionalists. Broadly, functionalists believe that identity tracks function rather than constitution: that you can identify X by focusing on what X does, rather than what X is made from. (Your front door is a ‘door’ because you can open it and go through it!) And, computational functionalists in particular, as Seth tells us, believe that “the kind of functional organisation that matters for mind in general, and for consciousness in particular, is computational in nature”. I won’t go into the many objections Seth raises to computational functionalism. But I found him particularly convincing on: 1) the difficulty of separating out what brains do, from what they are; 2) the difference between simulating something, and realising it; and 3) how surprising it is that people buy this focus on computation, when you think hard about what the brain is like. As he emphasises, for instance: “When we look inside a brain, we do not find anything like a sharp distinction between ‘mindware’ and ‘wetware’ of the kind we find between hardware and software in a computer”.

Having dismissed computational functionalism, Seth makes his positive argument. Here, he ties consciousness to the property of ‘being a living thing’, but leaves open the possibility for AIs to become sufficiently “life-like” to become conscious. And whilst I think ‘life-like’ is itself at risk of falling foul of Seth’s ‘simulation-realisation’ problem, I love his commitment to the relevance of life. This is largely because the pervasive focus of philosophers on human qualities like sentience and intelligence — in discussion of animal rights, as well as consciousness — often strikes me as second order to the significance of simply being alive.

Nonetheless, even though I agree with Seth that only living things can be conscious, and even though I’m happy to accept that the physical matter of AIs could one day replicate the physical matter of conscious living things, reading this paper hasn’t made me any more open to the idea that AIs could become conscious. This is because, unlike Seth, I’m not a physicalist. That is, I don’t believe that if scientists created a machine that perfectly physically replicated every detail of your body — from your hands, to your face, to your neurons, to your nerves — this machine would therefore hold the possibility of being conscious. Whereas, early in the paper, Seth lightly drops the massive claim that “implementing the neurobiological mechanisms underlying consciousness, at the right level of granularity, would by definition realise consciousness”.

Beyond our theoretical differences, however, my main criticism of this paper is simply that there’s too much scene-setting detail. I do get that this is how scientists write, however! And I admire them for it — from my vantage point of luxuriating in focusing on the cool bare arguments of philosophy. Anyway, if you think (wrongly) that the important question of whether ChatGPT can truly be your friend hinges on whether ChatGPT is conscious, then you’d better read this paper, written by a genuine philosopher-scientist.

2) I won’t do this often, but I’ve already subjected you to a lot of words on philosophy, and there are more to come below. So, beyond telling you that Eric Berger is probably my favourite contemporary space writer, all I’ll do is inform you of a seriously great new Berger piece, entitled Ranking the 25 Coolest Things in Space So Far During the 21st Century. (Its ranking is very convincing!)

3) As part of my ongoing practice of reading classic twentieth-century philosophy papers, this week I returned to a top contender for the most important: Edmund Gettier’s 1963 paper ‘Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?’. In only three pages — pretty much the only pages he ever published — Gettier argues that ‘JTB’ is not knowledge. And he does this in the face of many (if not most) of the philosophers before him.

In other words, Gettier argues that justification, truth, and belief do not combine to provide a sufficient condition for knowledge: you can believe X, you can be justified in believing X, and X can be true, but you might still not know X! Take the following example, invented by Roderick Chisholm.2 You’re in the field, and you see a sheep, so — somewhat unsurprisingly — you conclude that you know there’s a sheep in the field. Sounds ok, right? Well, no. It turns out that what you saw was not a sheep, but a dog dressed convincingly as a sheep! And it also turns out there was indeed a sheep in the field, but it was hiding, so you didn’t see it… Following Gettier, it seems you were justified in believing there was a sheep in the field, and it’s definitely true that there was a sheep in the field, but — surely — you didn’t know it to be the case.

At this point, I could offer you some more examples, because there are many. Indeed, these are some of the most famous examples in all philosophy: they’re literally referred to as ‘Gettier examples’ or ‘Gettier cases’. Instead, however, I’m going to tell you how to make your own. The trick is to know that Gettier’s argument depends on the following two claims. First, the claim that you can be justified in believing a false proposition. (Here, imagine that Mr X has a doppelganger, and this leads to an onlooker, Mrs Y, coming to some false but reasonable conclusion about Mr X: about his behaviour, or location, or whatever takes your fancy.) Second, the claim that if you’re justified in believing P, and you deduce correctly that P entails Q, then you’re justified in believing Q.3 (Here, cash out your Mr X example, to show that the difficulty in distinguishing between Mr X and his doppelganger could’ve led to Mrs Y ‘fakely knowing’ something about Mr X).

Lots of people have criticised Gettier, but it seems fair to claim that JTB has never been revived.

4) Having written last time about Daniel Dennett’s ‘Where Am I?’, I decided to stick with short stories that serve as thought experiments, and recently returned to Omelas. If you know of this place, then I hope you aren’t there permanently, either. As revealed by the story’s title — The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas (1973) — its author, Ursula Le Guin, forces us to think about the difference between two sets of people: those who remain in Omelas, and those who leave.

Omelas, she tells us, seems like a utopia. Not only do its inhabitants act as if they’ve achieved the kind of fulfilment that makes childish happiness seem thin, most of them simply have no need to take the life-enhancing drugs (which do wonders for one’s mind, body, acquisition of knowledge, and sex life) they’re legally permitted to access.

The apparent deep goodness of Omelas is by no means deep, however. This is because, as you probably already know, its persistence depends on the unbearable suffering of one particular child.4 The passage in which Le Guin describes the child’s situation is hard to read. But it’s surpassed, in its unbearable nature, by the passage in which she describes the ways in which the people who remain in Omelas attempt to justify their complicity in this act of child sacrifice. “Indeed”, Le Guin reveals, some of them even tell themselves that, “after so long it would probably be wretched without walls about it to protect it, and darkness for its eyes, and its own excrement to sit in”.

The Omelas question hangs, therefore, over this word ‘unbearable’. Not in terms of what counts as unbearable for ‘it’, the child. That much is clear. But rather, the full extent of the terrible trades that humans find it bearable to take, and what this means for our understanding of morality.

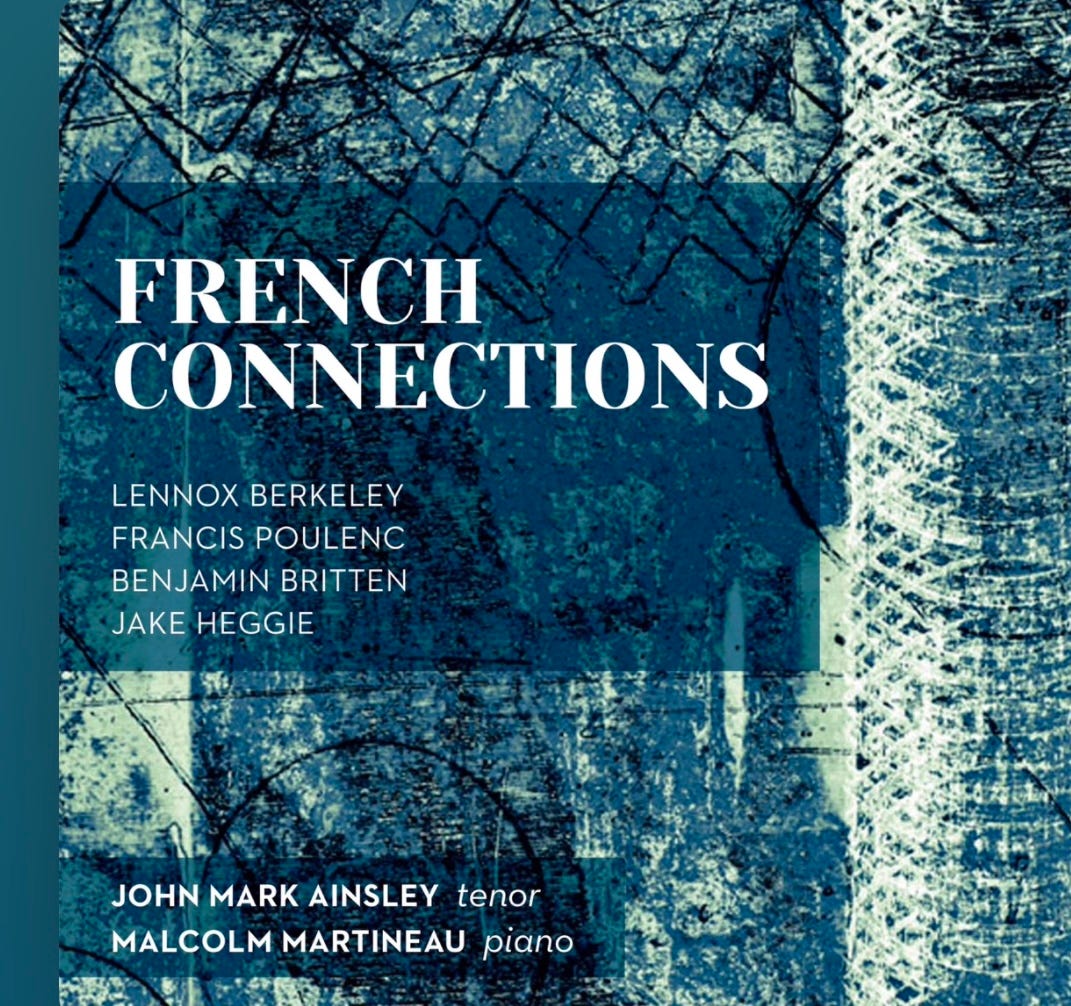

5) One of the pieces of music I listen to the most is this recording of Fancy by Francis Poulenc (1959). It’s well sung by John Mark Ainsley, and Malcolm Martineau’s accompaniment is excellent, as ever. But for me, here, the song is the thing. It’s Poulenc, in English, which catches your attention. (As does the sounding of its final bell.) It’s short, it’s simple, and it’s Shakespeare. It may be perfect.

I actually think Seth argues in the article that they will otherwise never become conscious. But he uses a locution based on ‘unlikely’ in the abstract, and I’d rather under-claim about his position that overstate it.

I’m sorry if I’ve got any of the details of this example wrong: I’m describing it from memory.

This is close to being a direct quote from Gettier. I’ve simplified it, and contracted it more generally, but you can something pretty similar near the bottom of p.121: Gettier, E. (1963). Is Justified True Belief Knowledge? Analysis, 23, 121-123.

If, like me, you’re obsessed by thinking about the moral status of consequentialism, then you’ll know this for sure.

Gettier's claim, that JTB is the 'traditional' analysis of knowledge, has recieved some pushback of late. For example, Maria Rosa Antognazza's recent book, 'Thinking With Assent', critiques the historicity of this claim (and the general approach of treating knowledge as a species of belief).

You probably came across her at KCL. Sadly, she passed away before the book was published.

Thanks for the post (and blog)–it's great!