five top things I read in 2024

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

TLDR:

What I Loved, Siri Hustvedt

The Universe As We Find It, John Heil; and Personal Agency, E.J. Lowe

How to Do Things with Words, J.L. Austin

Last days of the lonely interstellar spacecraft, Oliver Roeder

Capriccio selections, performed by Renée Fleming, Gianandrea Noseda, NSO

This is the latest in a regular Sunday series, although I’m forgoing my usual ‘over the past week’ limit, in honour of the coming end of 2024.1 As with previous editions, I’ll also move beyond ‘things I read’.

1) The book that struck me the most this year is easily Siri Hustvedt’s What I Loved — a 2003 novel chronicling the overlapping friendships and romantic loves of a New York art historian. Six months on, I continue to deliberate the theories Hustvedt advances through this novel, on topics ranging from parenthood to psychopathy to the trading of paintings. More directly, however, its characters have remained with me in a way I don’t usually find. I think this is largely because I tend to evaluate novels as an intellectual kind of art object. This isn’t to deny the intellectual calibre of Hustvedt’s novel! Nor is it to deny that I love novels, or that they’re a central source of beauty in my life. I’ve even cried at them many times — albeit never as much as when reading the opening chapter of the second part of What I Loved, on a train somewhere near Prestatyn.2 But I’ll admit I find it odd when people talk about disliking a novel because they find its characters unsympathetic. And I find it incoherent when people want to ascertain truths about fictional characters that aren’t to be found in the fixed world of their novels — truths about matters like, “Did they live happily ever after?” As soon as I finished What I Loved, however, I wanted its characters back. I wanted to learn more about these guys, who I now missed badly. I no longer think about this novel every day, but I’m yet to go for more than a week.

Honourable mentions for recent fiction I’ve read this year go to Brandon Taylor’s Late Americans (2023), Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Long Island Compromise (2024), and Paul Auster’s Baumgartner (2023).

2) Two philosophy books I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about in 2024 are The Universe As We Find It (2012) by John Heil, and Personal Agency (2008) by E.J. Lowe. These are books by two of my favourite people, who themselves had a wonderful friendship, so I am biased about these books.

In The Universe As We Find It, Heil advances his particular kind of ontological approach — an approach he describes as realist, particularist, naturalistic, and “from the gut” — through a pervasive focus on the relation between substances and properties. Substances, Heil argues, are bearers of properties, and properties are ways substances are. And if we accept this, he shows us, we can learn about the makeup of the universe in a way that coheres with scientific understanding as well as with our own experiences. I find reading this book a totalising experience: when I’m reading it, I’m fully inside its universe. Beyond strongly informing my views on ontology, I’ve learned a great deal about many things — from Descartes to infinity — by reading this book, which I’ve been doing as slowly as I can, chapter by occasional chapter, and will continue doing, over the next year or more.

Personal Agency is a different kind of book. Probably I think this, however, because rather than the sequential approach I’ve been taking with Heil’s Universe, I’ve been reading Personal Agency in a purposefully disordered manner. I’ve been spending some time thinking about freedom of action this year, and I often turn to Personal Agency when I’ve thought through where I stand on some issue, and feel the urge to know my dad’s response. So, whilst I will definitely read Personal Agency all the way through next year, in 2024 I have loved in particular its sections on causation and free will. I’m now fully convinced, for instance, that when I wave, my waving is the moving of my arm, rather than the moving of my arm being the thing that causes me to wave. And this example helps me to accept that agent causation is irreducible to event causation. I’m also now largely convinced that, because I agree with Dad that deliberation involves a whole series of free choices, I needn’t worry so much about the ‘randomness’ arguments against free will. This is reassuring to me.

Beyond substance, I’ve really enjoyed the writing styles of these books: styles which are different, but equally good (although, again, I am biased!). I put Heil’s Universe in my mental category of modern philosophy classics that are truly poetic, alongside David Lewis’s On the Plurality of Worlds. There are times with these poetic philosophy books when you feel like you’re reading a religious tract. I’m not religious these days, but I mean this as a compliment! There’s something transcendent about the style of these books, which adds to your reasons to be convinced. So it’s not a continental, ‘the style is the thing’, attempt at an exhaustive kind of reason, but rather that beauty comes here as a bonus, on top of rigorous and convincing argumentation. My dad’s writing, on the other hand, simply reflects how neatly and thoughtfully he spoke. He is fully within the clear, straight-up, sparse but dense, dry but funny camp,3 which is so typical of great analytic philosophy, and which is almost always my reading preference, for all kinds of writing. I’ve loved returning to both of these books, again and again, over the past year.

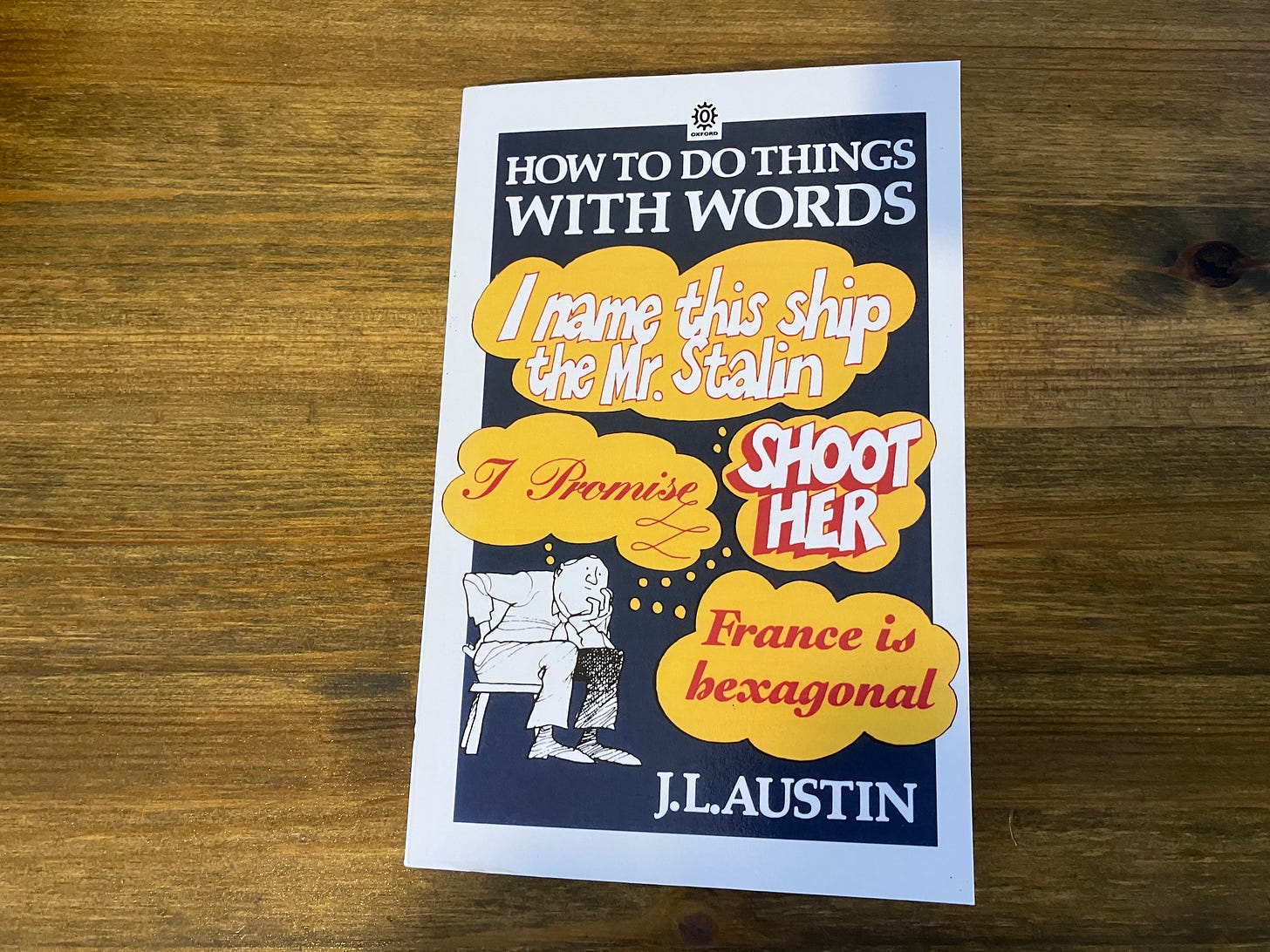

3) The other philosophy book I’ve returned to the most in 2024 is a book I wrote about in the first edition of this ‘top five’ series:

J.L. Austin’s How to Do Things with Words (1962) is one of the most influential philosophy books of the twentieth century. Austin argues that, generally, statements have been badly categorised: they’ve been incorrectly reduced to ‘statements of facts’, assessable in terms of whether they’re true or false. And that we can see this over-reduction really clearly when we consider the common phenomena of ‘performatives’. Performatives are utterances such as, “I name this ship ‘Rebecca’!”, and, “I bet you $10 Harris will win”. Austin tells us that performatives meet two conditions: 1) they don’t describe, or report, or do anything to make them the kind of statement that has truth value; and 2) their uttering is, or is part of, an action, beyond just ‘saying something’. So when you’re in the dockyard authoritatively shouting, “I name this ship ‘Rebecca’!”, you’re not describing what you’re doing, you’re actually doing it, and it’d be weird and wrong for someone to assign truth value to your combination of words. Austin tells us many other things about performatives. And it’s all very interesting, and I find lots of his arguments convincing. But beyond any of that, it’s a really rigorous and fun book. I find it comforting to read, and I like the cover of this edition. I’m listing it today, but I could’ve listed it most previous weeks of this year (if I’d begun writing this Substack earlier), as I’ve been going back to it a lot.

An honourable mention for recent philosophy books goes to Susana Monsó’s Playing Possum (2024), which I wrote about here and here. And also to Tommie Shelby’s The Idea of Prison Abolition (2022), which I’ll write about sometime soon.

4) The next slot on my list almost went to Brandon Taylor’s recent FT piece on tennis and loneliness, which I loved. But I’m unable to deny that the best FT piece I read this year was Oliver Roeder’s ‘Last days of the lonely interstellar spacecraft’. Indeed, as I wrote a few weeks ago, the Roeder piece is ‘one of the best pieces of any kind of journalism I’ve ever read’. This feels a bit unfair to Taylor, however, and I’ll definitely write about his tennis piece at some point, perhaps alongside the great tennis sections of his novels and Substack. For now, however, here’s what I wrote about Roeder:

The best piece of space journalism I’ve read this year — indeed, one of the best pieces of any kind of journalism I’ve ever read — is Oliver Roeder’s ‘Last days of the lonely interstellar spacecraft’, for the FT. It’s a long account of the ever-ongoing journeys of the twin Voyager space probes, as they “now speed through the cold dark of interstellar space, beyond the influence of our Sun”. It reads like a restrained cross between William Gibson and William Blake: as with Vonnegut [who I’d also been writing about that week], every sentence counts, and somehow Roeder ties together the unworldly romance of space travel with the exactitude of an investment report. It’s fantastic.

5) Finally, I’ll move away from reading. Honourable mentions for ‘live music I listened to in 2024’ go to this CSO Liszt and Bruckner concert, Glyndebourne’s Zauberflöte, Arturo Sandoval at GMU, and the performance of Beethoven 7 I heard the Joe Policastro Trio play at the Green Mill jazz bar in Chicago. And, among a load of mediocre-to-good options, the Theatre Royal Haymarket’s A View from the Bridge probably wins the plays category, followed closely by Rosencrantz and Guilderstern at the DC Arts Center. The best live aesthetic experience I had in 2024, however, was also something I’ve already written about here:

A few weeks ago, I went to see Renée Fleming sing the final scene from Strauss’s Capriccio at the Kennedy Center in DC (NSO, Noseda). As with the couple of previous times I’ve heard Fleming, parts of it felt time-stopping. Her voice has a twisted tightness and a stretchy freedom, the combination of which is hard to describe, but I think can be heard particularly easily in this folksong recording. Nobody is better suited to the build-up to Strauss’s stratosphere. That said, whilst it seemed a risk to follow Fleming-Strauss with anything, the performance of Brahms 1 that came next was just as good. If you buy the motivic/melodic composer distinction (think Bach and Beethoven and Bruckner, versus Handel and Mozart and Brahms), then this performance — with its emphasis on the percussion and bass line — advanced the counter-argument to Brahms’ melodic status.

For completion’s sake, my top five from the last week are: Wuthering Heights (which I hadn’t read in twenty years), Rawls’ Theory of Justice (which I return to most weeks), Tyler Cowen’s The Age of the Infovore, William Skidelsky’s Federer and Me, and O kühler Wald by Brahms.

Yes, Larkin is my favourite poet.

Heil’s writing also exemplifies these kinds of great qualities.

Thanks Rebecca for reminding me of these, and a long talk with Jonathan about Personal Agency including how his view that the concept of cause may require experience of agency could serve as the beginning of a transcendental argument. His generosity with time seemed to be based on a level of discipline and self-organisation I could only envy. Best wishes with your work

I love that you can talk to your dad through his book