TLDR:

How to Do Things with Words, J.L. Austin

A Pale View of Hills, Kazuo Ishiguro

The Promising Game, R.M. Hare

Playing Possum: How Animals Understand Death, Susana Monsó

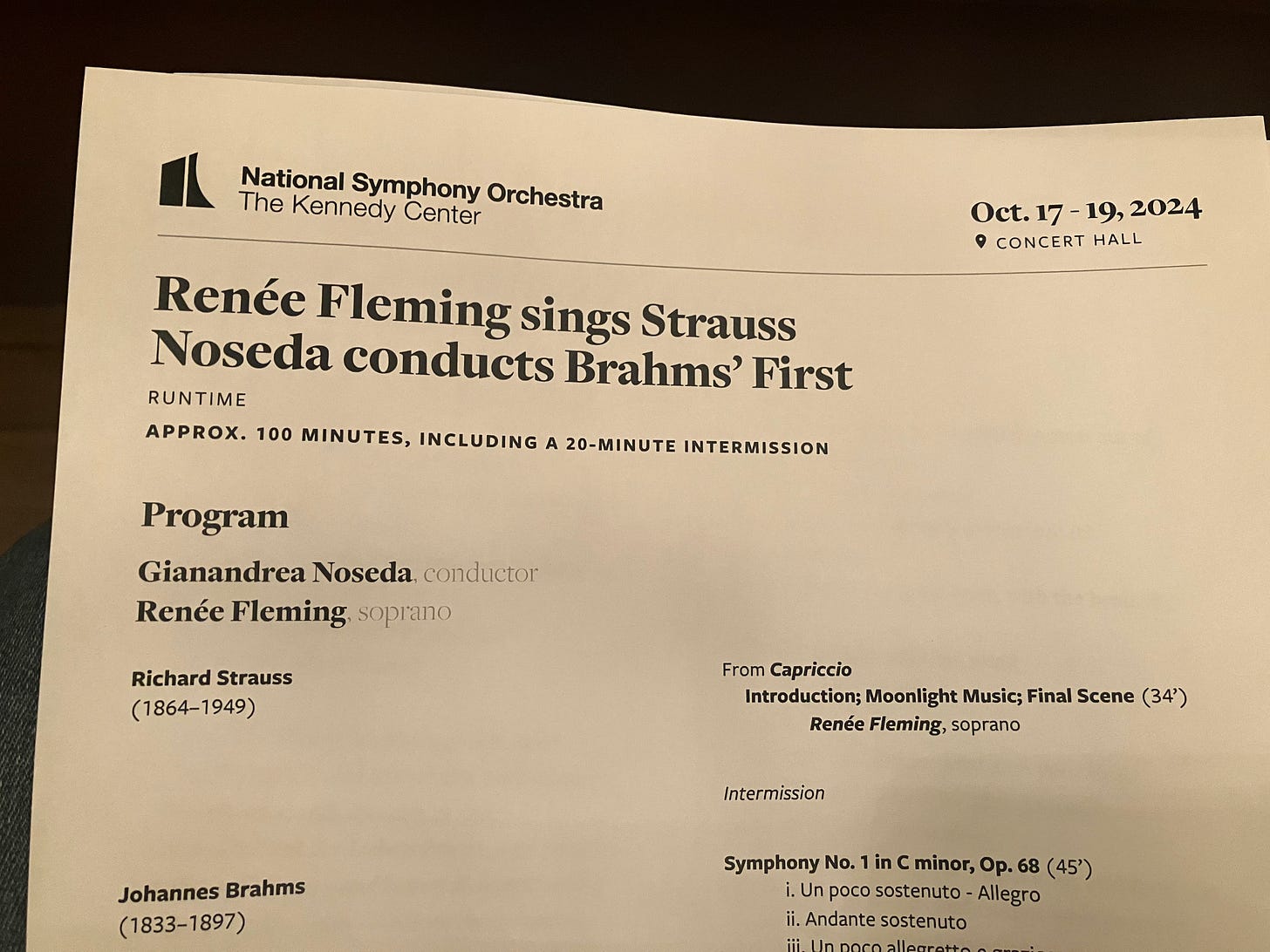

Capriccio selections and Brahms Symphony No. 1, performed by Renée Fleming, Gianandrea Noseda, NSO

I like reading and I like ranking, so this is the first in a regular series. Technically, today’s post includes only four things I’ve been reading, as the fifth is something I listened to. So maybe you can expect some looseness in future, too.

1) J.L. Austin’s How to Do Things with Words (1962) is one of the most influential philosophy books of the twentieth century. Austin argues that, generally, statements have been badly categorised: they’ve been incorrectly reduced to ‘statements of facts’, assessable in terms of whether they’re true or false. And that we can see this over-reduction really clearly when we consider the common phenomena of ‘performatives’. Performatives are utterances such as, “I name this ship ‘Rebecca’!”, and, “I bet you $10 Harris will win”. Austin tells us that performatives meet two conditions: 1) they don’t describe, or report, or do anything to make them the kind of statement that has truth value; and 2) their uttering is, or is part of, an action, beyond just ‘saying something’. So when you’re in the dockyard authoritatively shouting, “I name this ship ‘Rebecca’!”, you’re not describing what you’re doing, you’re actually doing it, and it’d be weird and wrong for someone to assign truth value to your combination of words. Austin tells us many other things about performatives. And it’s all very interesting, and I find lots of his arguments convincing. But beyond any of that, it’s a really rigorous and fun book. I find it comforting to read, and I like the cover of this edition. I’m listing it today, but I could’ve listed it most previous weeks of this year (if I’d begun writing this Substack earlier), as I’ve been going back to it a lot.

2) A Pale View of Hills (1982) is Kazuo Ishiguro’s first novel. It’s a short, realist, non-linear, ‘psychological’ novel, narrated by a woman named Etsuko. Etsuko lives in the UK, in the house she once shared with her husband and daughters, but much of the novel is set in Nagasaki, where she lived before, during, and after the atomic bomb’s devastation. Plot-wise, it’s a confusing book, and apparently Ishiguro himself has discussed a (pretty serious) plot flaw, but to my mind, this doesn’t detract from its coherence. I get what Ishiguro is trying to do (I think!), and it fully gets me, regardless of structural problems. This made me reassess the necessities of great fiction. Moreover, Ishiguro’s writing style here attains that elusive quality of non-distracting beauty: you forget you’re reading something that’s been written, whilst also somehow taking in how graceful and tight the writing is. I don’t think I’m unusual in loving some of Ishiguro’s novels whilst having given up on others (The Unconsoled is one of the novels that disappointed me most in my life). A Pale View of Hills is the best of his I’ve read.

3) I’m currently making my way through reading (and in some cases rereading) a load of classic twentieth-century philosophy articles. In The Promising Game (1964), R.M. Hare takes on the ‘is-ought’ relation, and in particular John Searle’s position that we don’t need “evaluative statements, moral principles, or anything of the sort” to conclude that we ought to keep the promises we make.1 One of the funniest things I read this year was the ‘my girlfriend goes to another school’ explanation that Hare gives, at the start of Freedom and Reason, about why he won’t include a “full-scale rebuttal” of his critics:

Some of the side comments in The Promising Game are also amusing, and funnily it’s the ‘positive things’ here that are minimal. Having taken Searle’s position apart, Hare gives us just one Kantian paragraph on his “own reasons” why we should keep our promises. Beyond these meta matters, however, I particularly enjoyed Hare’s discussion of the ‘institution of promising’: the idea that to be able to make a promise, sufficient people around you must have accepted some principles of promising. It’s a great article, but make sure to note down the referents of 1, 1a, 1a’, 1a’*, etc, or you’ll be endlessly turning back pages.

4) Susana Monsó’s Playing Possum is the 2024 philosophy book I enjoyed reading the most, so far. It’s a book about animals and death, and particularly, whether non-human animals can conceive of death. I remain unconvinced that we can know such a thing, but, as with How to Do Things with Words, I think Playing Possum is a great example of someone doing philosophy really well and also accessibly. Ok, it’s much more accessible to the modern public than Austin (which is hardly surprising), but it’s also unabashedly technical. For instance, to advance a minimal concept of death, Monsó first advances a theory of concepts. The book is also both coherent and through-composed; it’s neither one of those books that jumps around superficially, to include comments on everything recently written, on any topic vaguely related, by anyone at all important (to try to ensure good reviews), nor is it one of those books with three simple ideas repeated in endless different ways (to try to give boring people things to talk about at dinner parties). In particular, Monsó writes convincingly about the weaknesses of standard approaches to animal thanatology: especially, the problems of anthropocentrism and anthropectomy,2 and the tendency to conflate the question of whether animals can understand death with the question of whether animals can grieve. What I valued most about this book, however, is its amazing animal stories.

5) A few weeks ago, I went to see Renée Fleming sing the final scene from Strauss’s Capriccio at the Kennedy Center in DC (NSO, Noseda). As with the couple of previous times I’ve heard Fleming, parts of it felt time-stopping. Her voice has a twisted tightness and a stretchy freedom, the combination of which is hard to describe, but I think can be heard particularly easily in this folksong recording. Nobody is better suited to the build-up to Strauss’s stratosphere. That said, whilst it seemed a risk to follow Fleming-Strauss with anything, the performance of Brahms 1 that came next was just as good. If you buy the motivic/melodic composer distinction (think Bach and Beethoven and Bruckner, versus Handel and Mozart and Brahms), then this performance — with its emphasis on the percussion and bass line — advanced the counter-argument to Brahms’ melodic status.

I’m quoting Hare on Searle, here (p.399), not Searle himself. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23940466

Monsó tells us that “if anthropomorphism is the mistaken attribution of a human-typical characteristic to an animal, anthropectomy would be the mistaken denial of a human-typical characteristic to an animal”, p.46.

Looking forward to more in this series. Thank you.

I enjoyed this. What format do you read philosophy papers in? I find philosophy almost incomprehensible without printing it off, which has its own inconveniences... I wish there were more books which compiled classic papers in different fields along with commentary and explanatory notes (something like this: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262045308/ideas-that-created-the-future/).